The Evidence Room: Making Visible the Unimaginable

How do you express the inexpressible?

How do you prove that something horrible - traumatic, unspeakable - really happened?

How do you answer those who would rather believe that you were just imagining things - or, worse, making it up in order to seek attention?

Step inside The Evidence Room, and you will find out.

It should be obvious that I am many things besides a blogger. While I can wax philosophical about this, saying that I am a daughter or a sister or a friend, for today, I am a volunteer Gallery Interpreter at the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto. The post comes, understandably, with a number of perks - not least of which is the joy that comes with sharing my love for history and world cultures with visitors. However, part of working in a museum environment is that I am oftentimes left with more questions than answers: sometimes, these questions excite me and inspire me to try to find out more, but other times, I wonder just how much I ever can know.

Case in point: The Evidence Room.

This exhibition is an art installation put together by a team from the University of Waterloo School of Architecture. Their goal? To interrogate the ethics of architecture by examining the infrastructure and design of Auschwitz-Birkenau, the infamous Nazi death camp.

The exhibit's creators were inspired by a court case in which author and historian Deborah Lipstadt was sued for libel by an eminent Holocaust denier. In 2000, the lawsuit was settled in Lipstadt's favour after blueprints and other pieces of architectural documents from Auschwitz-Birkenau were presented as proof that the camp had been designed and constructed with the intent to kill.

(Note: although I am aware of said Holocaust denier's identity, the ROM has chosen not to publish it in any of its materials, and thus I also refrain from doing so here.)

I cannot claim to understand what drives people to deny that the Holocaust happened. I have, over the years, seen and heard snippets that hint at some great Jewish conspiracy, or that simply say that the Holocaust pales in comparison to other atrocities that take place in the world today.

Oftentimes, I try not to think too much on the more insidious of these voices. Instead, I would rather believe that Holocaust deniers are simply...overwhelmed: choosing, like little children, to cover their eyes and look away from what frightens them. After all, the immense loss of life in such a short period of time is horrific to think about as it is - even more so to realize that it was deliberately done, by normal, sane people just like you and me.

Yet, when dealing with these moments in history, we cannot afford to shy away. There are times when we as human beings must face our darkest sides head-on: to recognize them for what they are so that we never allow them to rise up again.

That was the mindset I adopted when I visited The Evidence Room for the first time. I had heard other volunteers talking about how it could be an intensely emotional space for staff and visitors alike, so I was not entirely sure what to expect.

How would I react?

The first thing I noticed upon entering was the colour. Everything inside the main exhibit room was white - and that took me entirely by surprise.

White is a significant colour in many different contexts, and for me, I think of cleanliness, purity, and light. Perhaps that is why the choice of an all-white colour scheme in The Evidence Room came as a shock to me. See, when I think of World War II and the Holocaust, I imagine a world in greyscale: the type that you see in the black-and-white photographs of the day. And, yes, while white is an important colour in those pictures, I imagine the extermination camps in shades of grey, oftentimes veering towards black: a world in which darkness reigns.

I have asked fellow volunteers for their thoughts on why The Evidence Room is mostly white, and answers vary depending on their personal interpretation: the Nazi party's obsession with racial purity, the sterility of a hospital morgue, even the fact that white is the traditional colour of mourning in Chinese culture. Finally, one of my colleagues gave me an intriguing clue: the white evokes plaster casts that are used in forensics and archaeology. Since The Evidence Room was created to question the ethics of architecture - the fact that architects' designs could be used to provide life and shelter, but also to kill - the use of white is a condemnation. It marks the Holocaust, as exemplified by Auschwitz-Birkenau, as a crime, and the architects who designed it the criminals.

Perhaps this is why, when I first noticed the colour of the exhibition, I thought it looked clinical, sterile...devoid of life. This sense was compounded by the second major point I noticed in The Evidence Room. As stark as the content is, the exhibition is not transparent. As a visitor, you have to stop and think about what you are seeing, and as you do, the horror gradually sinks in.

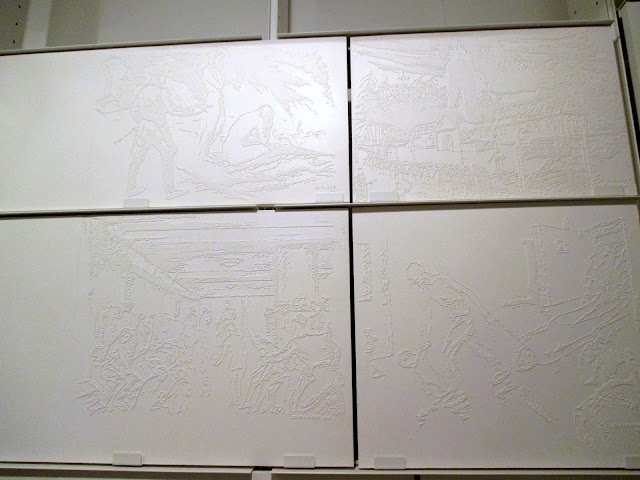

For example, I noticed that many of the images on the walls were reliefs from 2-dimensional images, meaning that what was depicted in them was not immediately apparent at first glance. From a stance of user-friendliness, this was problematic. It was far too easy to simply fail to notice there was anything on the wall panels, and people could simply walk past without registering what they were seeing.

In hindsight, though, I believe that this demand to visitors to pause, peer closely, and then understand what they are seeing is part of the point. White on white, without the presence of clear shadows, is hard to decipher, but by using that colour scheme, the creators of The Evidence Room make it clear to viewers that they should not just pass these images by, but should stop and take a closer look: sooner or later, their content will become decipherable, visible, comprehensible.

Another way that The Evidence Room performs this function is through the larger pieces scattered throughout the room.

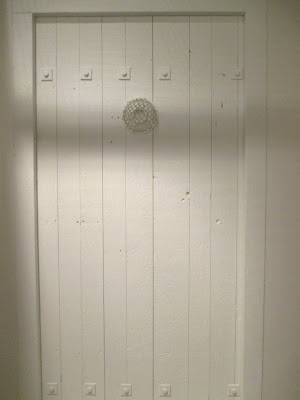

Try it for yourself: can you tell what you are seeing?

These larger sculptures were all objects that would have appeared inside the gas chamber of an extermination camp like Auschwitz-Birkenau. For instance, one of the pieces (top row of photographs) was a closed door, placed so that visitors could look closely at both sides. I noticed almost immediately that there was only a latch on one side, presumably the outside, whereas the side that would have been facing into the gas chamber had an entirely smooth surface: escape would have been impossible without breaking down the door. Another such sculpture (bottom left) was one I spent a particularly long time observing, because of its level of detail. This was a replica of one of the pillars inside the chamber through which Zyklon-B pellets would have been lowered; although archival photographs show that these pellets were stored inside a canister, the display in The Evidence Room uses a basket, making the - admittedly fake - pellets more noticeable to visitors.

However, as with the engravings on the walls, I noticed that these sculptures are not immediately transparent. It takes a moment of reflection and careful observation in order to fully understand that The Evidence Room was an approximation of a gas chamber. While I, as a volunteer at the Royal Ontario Museum, knew in advance what to expect, I also saw that for a number of visitors, the gravity of the exhibition went unnoticed. Granted, while I was inside, I saw some who, upon entering the room, stumbled in surprise at what was in front of them, the realities of the Holocaust sinking in. However, in my few minutes of observation, I also saw a small child running around the door sculpture, ducking behind it in a game of peek-a-boo with her guardians.

Maybe, in hindsight, that's not a bad thing. I know that as someone who is aware of the Holocaust on an intellectual level, my response would be different from that of an innocent child - would be different from that of a Holocaust survivor or his/her descendants. We all approach history through our own individual lenses, after all.

And while, initially, I bristled at the little girl's antics, looking back, as I write this blog, I cannot help but wonder: is her ignorance really so bad?

Doubtless, there is a world of difference between a child's naive innocence - seeing a door as simply a door, and not as a sinister object from an extermination camp - and the stubborn arguments of a Holocaust denier. However, in my mind, I cannot help but return to these two individuals: the scholar whose claims that the Holocaust never happened started the entire judicial and creative process that culminated in The Evidence Room, and the young girl who now, in a better world, could play happily without fear. I wonder if this, in fact, is the genius behind The Evidence Room: by proving that atrocities like the Holocaust happened, we could work towards creating a safe space for generations to come.

So let the children play...because there is still some good in this world.

The above blog post is part of the ongoing series Memorializing History, which looks at the different ways in which people engage with historical events and issues. To access a master list for this and other series, click here.

Resources

Moore, Deborah Dash. "Deborah Lipstadt." Jewish Women: A Comprehensive Historical Encyclopedia, Jewish Women's Archive, 1 March 2009, https://jwa.org/encyclopedia/article/lipstadt-deborah. Accessed 30 July 2017.

"The Evidence Room." Royal Ontario Museum, n.d., http://www.rom.on.ca/en/evidence. Accessed 30 July 2017.

Image Credits

All photographs (c) Kitty Na

.jpg)

Comments

Post a Comment